March 27, 1963. It’s not a date that might live long in the memory of anyone under 60, but the impact of this date is something that still has a noticeable impact on how we travel today.

Dr Richard Beeching, the Chairman of the British Railways Board, had been tasked by the Transport Secretary of the time, Ernest Marples, and the Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan, to produce a report containing recommendations on how British Rail could move from significant losses to making money. After all, by 1962, despite the pre-report closure or conversion to freight-only of 3,318 miles of railway, the financial situation facing British Railways was incredibly bleak. I

It was reported at the time that after the mostly disastrous 1955 Modernisation Plan, which sought to modernise British Railways at a cost of £1,240 million and bring British Railways back to profit by 1962, the opposite was true. The railways weren’t even able to pay the interest on its loans, with losses reaching £104 million by this year, equivalent to £2.36 billion today. On top of that, it was a time when the train was increasingly a relic of yesterday in a world where road transport was now king. Freight traffic had fallen, and more and more people were able to get to where they wanted to with the advent of affordable car ownership and mass investment in roads.

This was the day the report known as ‘The Reshaping Britain’s of Railways’, better known as the ‘Beeching Report’ or the ‘Beeching Cuts’ was published. It had been expected that a good chunk of Britain’s railways would be rationalised or closed, but the recommendations in the report led to howls of outrage from many communities facing the reality that their railway would be no more.

It could safely be said that some of the cuts were logical, or even inevitable, particularly where there was unnecessary route duplication; a product of the Victorian railway boom where railway lines were sometimes built to stop the opposition from building a line through it or indeed areas which had two rival companies trying to get the same passengers.

One example of such duplication was in Bodmin, which despite being a relatively small town at the time, had three railway stations. Bodmin North, a terminus for LSWR and later Southern Railway services to Wadebridge and Padstow, originally built in 1834, Bodmin Road (now Parkway), which was on the Great Western Mainline, opening in 1859, and Bodmin General, built by GWR in 1887 in order to gain access to Bodmin town centre and connect with the LSWR line at Boscarne Junction.

By the 1960s, Bodmin North (now the Berrycoombe Road Cornwall Council car park opposite the Original Factory Shop) was relegated to a shuttle service to Boscarne Exchange Platform, with passengers changing at this location to carry on their journeys to Wadebridge and beyond.

However, back to March 27, 1963, and this is the day where Dr Beeching publishes his findings and recommendations to the public and his Government paymasters. From here, it would be the Government who would take decisions based on the report, deciding what to close and what to keep, as well as implementing other proposed reforms detailed in the report such as replacement bus services in place of the closed lines, proposed reforms to handling freight and investing in diesel locomotives with the elimination of steam.

It also set in motion a chain of events that would tell a tale of two parts of Cornwall post-Beeching; North Cornwall, which was left with no railway services at all, and South East Cornwall where two lines threatened with closure were saved.

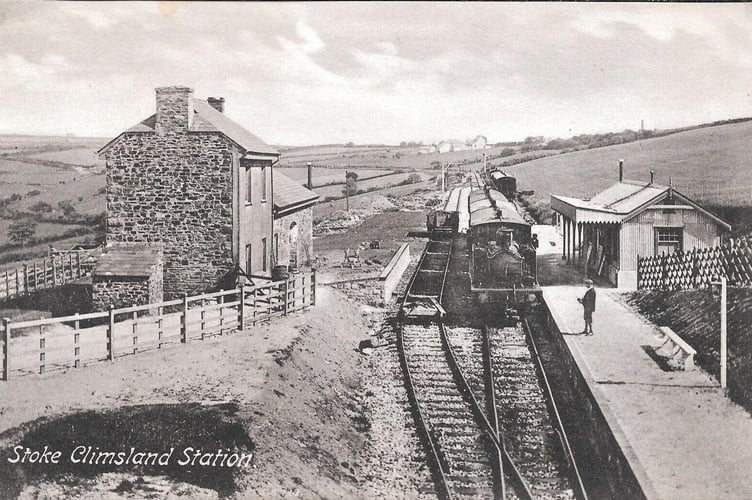

Prior to nationalisation in 1948, North Cornwall was very much the territory of the London and South Western Railway, better known as LSWR, and after 1923, the Southern Railway. While the Great Western Railway mainline, still in use to this day, linked Cornwall to Plymouth via a route going through the South East of Cornwall and over the Royal Albert Bridge, the LSWR route, often referred to as the Withered Arm, connected Cornwall with Exeter and beyond via a route which went from Bodmin to Wadebridge and onto Delabole, Camelford and Launceston before going onto Halwill Junction, where it met the railway line from Holsworthy and going onto Meldon, Okehampton and finally, Exeter. There were also branch lines connecting Bude and Padstow with this railway line.

A relatively circuitous route covering a lot of rural parishes, it had been identified in the Beeching report that because of the size of the populations served by the railway and the length of line, it took to connect them, this would be the railway to close, with the Great Western Mainline to be retained. There had also been concern about the condition of Meldon Viaduct, which by this time was in a poor state of repair and subject to a weight restriction.

The Beeching Report recommended that the Withered Arm was to be condemned to closure in almost its entirety, an action agreed upon and instructed by the Government. Bodmin Parkway to Bodmin General and onwards to Wadebridge (as well as the non-passenger Wenfordbridge line) survived as a freight line until 1983 (Wadebridge closed in 1978) thanks to the clay dries at Wenford and the Okehampton to Exeter line being retained for passenger usage until 1972 and for freight afterwards.

The line between Bodmin North and Boscarne as well as Padstow to Wadebridge closed on January 30, 1967, while the lines between Bude to Holsworthy, Halwill to Okehampton, Halwill to Launceston and Holsworthy to Meldon Junction all closed in October 1966.

As per the terms of reference upon which it was requested, the Beeching report made no consideration of the impact that a closure of a railway line would have on the communities being left behind, but rather, it solely examined the railways on a purely economic basis. If it didn’t make money, it was potentially in the firing line, and if it disconnected communities, tough luck.

During the 1964 General Election, which saw the electoral defeat of Harold Macmillan and the Conservative government which had commissioned the report and started the process of implementing its recommendations, the Labour Party, led by Harold Wilson pledged to halt the “Beeching closures” as it was now known and reverse them. However, after winning the election, the now Labour government did the exact opposite; they accelerated the cuts, with the majority of the closures which took place in the 1960s taking place after 1964.

After presiding over approximately 2,050 miles of closures since becoming Minister for Transport in late 1965, Barbara Castle couldn’t avoid the increasingly deafening demands from the communities facing the axe of the railway lines any longer. While not every community would get to keep what was left of their railways, some would see salvation in the Transport Act 1968, which permitted the introduction of Government subsidies to subsidise railway lines deemed socially necessary but unprofitable. Although, some that were recommended to be saved in the Beeching report, such as the Okehampton to Exeter line, were closed anyway.

It would be this partial reverse turn that would see two branch lines in South East Cornwall spared from their rapidly approaching execution; the Liskeard to Looe and the Gunnislake to Plymouth branch lines.

For Gunnislake to Plymouth, a mostly single-track railway which had previously gone on towards Tavistock and Callington, sections which closed in November 1966, its salvation came not so much from any status of importance but the fact the local road network was considered extremely poor. It had been listed for closure in the Beeching report. To this day, the line, now known as the Tamar Valley line, still remains although its methods of working are still distinctly Victorian!

Like the Tamar Valley line, the Liskeard to Looe line, also a single-track branch line mostly built on the remains of the former Liskeard to Looe Union Canal was facing closure after the Beeching report recommendations. The salvation of this railway line was very much close to the wire, being saved on September 20, 1966, merely two weeks before it was scheduled to close permanently.

Its retention came thanks largely to the popularity of Looe as a holiday destination. Castle considered that the road network in the area was not sufficient to cope with the heavy holiday traffic which the area saw each summer.

Describing the potential railway lines closure as ‘the economics of bedlam’, upon announcing that it would be saved, along with St Ives to St Erth railway line, Castle said: “Several of my decisions affect holiday areas. I have refused to close the branch lines serving St Ives and Looe in Cornwall. In spite of the financial saving to the railways, it just wouldn’t have made sense in the wider context to have transferred heavy holiday traffic onto roads which couldn’t cope with it. Nor would extensive and expensive road improvements have been the answer. At St Ives, these would have involved destroying the whole character of the town. At Looe, they could not have avoided long delays in the holiday season. It would be the economics of bedlam to spend vast sums only to create greater inconvenience.”

Sixty years on from the Beeching report and the impact of what came next still looms large on the communities it affected, even if little remains of the railway which preceded it. After all, how much would a railway service to Padstow or Bude help with the summer holiday chaos?